The case of the man known publicly as SLD continues to stand as one of the most confronting and complex criminal matters in Australian legal history. More than two decades after the murder of three-year-old Courtney Morley-Clarke on the NSW Central Coast, SLD remains under close judicial and correctional scrutiny, long after completing his original prison sentence.

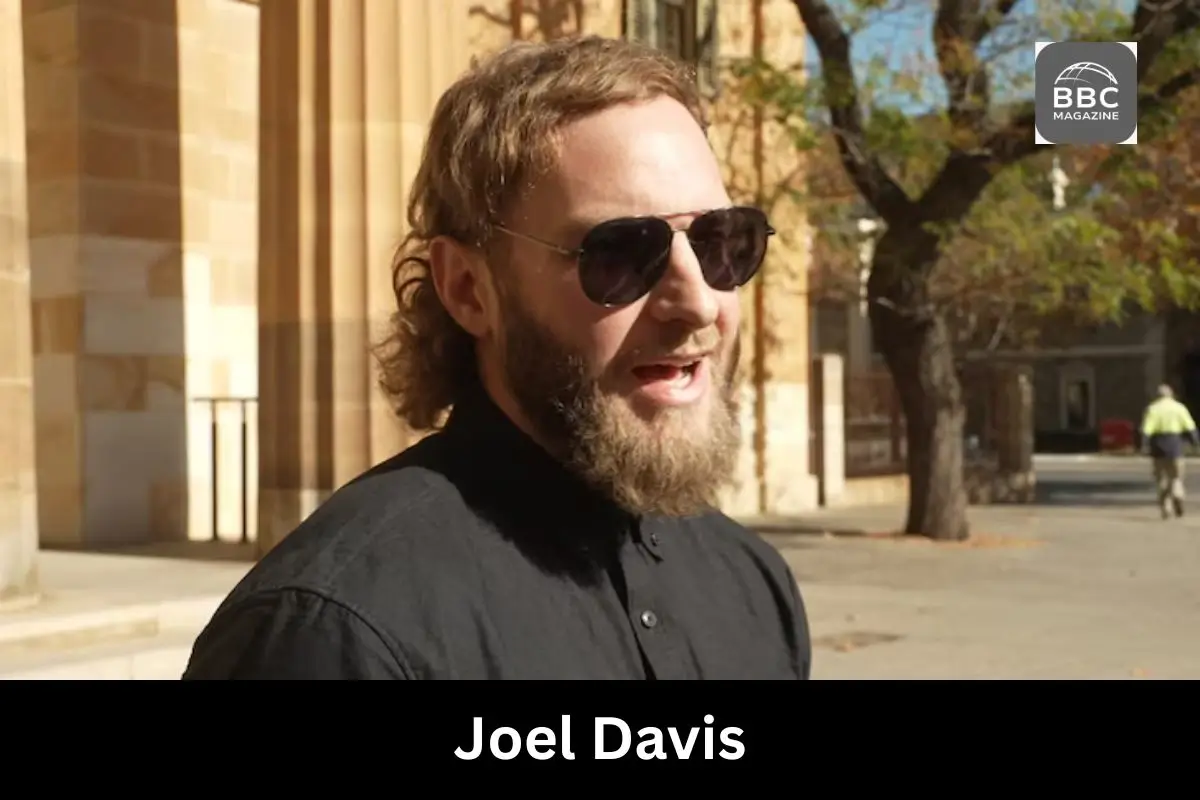

First convicted in 2001 at the age of 13, SLD became Australia’s youngest convicted murderer. His crime shocked the nation not only because of the brutality involved, but because it was carried out by a child. Since then, the case has evolved beyond the original homicide, extending into difficult questions about rehabilitation, risk management, post-sentence supervision and community safety.

Following his release from prison in April 2023 after serving 22 years, SLD was placed under an Extended Supervision Order. Less than a year later, his conduct at Bulli Beach in the Illawarra would bring him back before the courts, reigniting national attention and reopening public debate about how Australia manages offenders who committed extreme crimes as minors but live as adults under supervision.

A case that continues to follow one offender decades later

More than two decades after one of the most disturbing crimes in Australian criminal history, the man known publicly as SLD remains under intense judicial scrutiny. In October 2024, the New South Wales District Court ruled that he breached strict post-release supervision conditions by approaching a woman and her young child at Bulli Beach on the Illawarra coast.

The decision did not reopen the 2001 murder that made SLD Australia’s youngest convicted Sld killer. Instead, it focused on how the justice system manages risk when a person who committed an extreme crime as a child re-enters the community as an adult. The case now spans childhood homicide, decades of imprisonment, psychological assessment, supervised release, breach proceedings and a failed attempt by the state to keep him detained.

The murder of Courtney Morley-Clarke in 2001

In January 2001, three-year-old Courtney Morley-Clarke was put to bed in her family home on the NSW Central Coast during a hot summer night. When her father woke the following morning, her bed was empty. A screen door and side gate were open, and her nightdress was found outside.

Police later established that Courtney had been abducted from her bedroom and murdered by her 13-year-old neighbour. During police interviews, the boy confessed to the killing and made statements that deeply disturbed investigators, including claims that the murder was practiced for future killings. He also admitted that he had contemplated killing other children.

At just 13 years and 10 months old, he became Australia’s youngest person ever convicted of murder. Because the offence was committed while he was a minor, his identity was permanently suppressed. In court records and media reporting, he has since been referred to only by the pseudonym SLD.

Sentencing and growing up in custody

SLD was sentenced to a lengthy term of imprisonment and ultimately spent 22 years in custody. His teenage years were spent in juvenile detention before he transitioned into the adult prison system.

Later court proceedings heard that he effectively grew up behind bars, with limited exposure to normal schooling, employment, relationships or independent living. Psychiatric assessments tendered in subsequent hearings described the long-term effects of institutionalisation from childhood, including delayed emotional development and difficulty understanding ordinary social boundaries.

Release under an Extended Supervision Order

In April 2023, after completing his sentence, SLD was released from prison at the age of 36 under an Extended Supervision Order imposed under New South Wales law.

Extended Supervision Orders are preventative measures rather than additional punishment. They are designed to protect the community by tightly regulating the behaviour of offenders assessed as posing an ongoing risk. The orders allow a person to live in the community, but under strict controls enforced by Corrective Services.

SLD’s supervision order placed firm limits on his movements and conduct. One of the most significant conditions prohibited him from associating with children under the age of 18. He was also subject to close monitoring and regular contact with supervising officers.

The Bulli Beach incident in October 2023

On 23 October 2023, SLD was taken back into custody following an incident at Bulli Beach in the Illawarra region.

An off-duty corrections officer contacted police after observing SLD interacting with women who were accompanied by young children at different locations along the beach. The officer reported seeing SLD speak to a woman holding a child near a children’s pool, approach another woman and child at an outdoor shower, and later engage with a third woman and child near an outdoor seating area.

Police were only able to identify one of the women involved. She later told the court that SLD approached her and asked questions about her toddler’s physical appearance. He also asked whether the child’s father was present at the beach.

Following these reports, SLD was arrested and charged with three alleged breaches of his supervision order.

The legal dispute over the meaning of “associate”

The District Court trial in Wollongong focused heavily on how the word “associate” should be interpreted within the supervision order.

The prosecution argued that the term needed to be read in a way that reflected the protective purpose of the order, particularly given SLD’s criminal history and assessed risk. The defence contended that the word was ambiguous and that brief public interactions did not necessarily amount to prohibited association.

Judge William Fitzwilliams acknowledged that the issue was legally complex and noted that the term had not previously been judicially considered in this precise context. He cautioned against relying too narrowly on dictionary definitions and instead examined how the word functioned within the broader intent of the order.

The District Court’s findings

In October 2024, Judge Fitzwilliams delivered his verdict in the Wollongong District Court.

Of the three alleged breaches, the court found that one breach had been proven beyond reasonable doubt, while the remaining two had not met the required legal standard.

The judge found that, in the second incident, SLD had freely and voluntarily initiated a conversation with a woman while being aware that her toddler-aged child was physically present and dependent on her. He ruled that SLD deliberately chose to ask questions about the child and comment on the child’s appearance in circumstances where the child’s presence was obvious and unavoidable.

Judge Fitzwilliams concluded that the supervision order required a “connection of substance”, rather than mere proximity, and that this threshold had been met in the second incident. He stressed that the not-guilty findings on the other charges were not a criticism of the off-duty corrections officer who reported the behaviour.

SLD’s explanation following his arrest

During the trial, the court heard a recorded telephone conversation between SLD and his Corrective Services supervising officer following his arrest.

In the call, SLD said that his intention had been to speak with adult women and that he was attempting to secure a date. He denied that he intended to engage with children.

The court accepted that this explanation was raised but found that intention did not outweigh the objective facts of the interaction or the strict obligations imposed by the supervision order.

Bail status and further court appearances

Following the guilty verdict, no application for bail was made. SLD remained in custody while awaiting sentencing.

ABC reporting also noted that SLD was expected to appear in court again the following day on a separate matter, highlighting the extent to which his post-release conduct remained under judicial scrutiny.

Police Investigation Into the 2001 Murder

Police investigations into the disappearance of Courtney Morley-Clarke began in the early hours of January 2001 after her parents discovered she was missing from her bed. Initial concerns that the toddler may have wandered outside quickly faded when officers observed signs of forced entry, including a damaged screen door and an open side gate.

A large-scale search was launched across the neighbourhood and surrounding bushland. Within hours, police attention turned to nearby residents, including a teenage boy who lived close to the Morley-Clarke family home. Officers were alerted after his parents reported that he had been absent from their house during the night.

When questioned, the boy initially provided inconsistent accounts of his movements. He claimed he had been walking outside and later suggested he had encountered Courtney while she was already out of the house. Police searches based on locations he identified failed to locate the child, raising further suspicion.

Under continued questioning, the boy eventually confessed. Police were led to the location where Courtney’s body had been left, concealed in bushland not far from her home. Investigators established that she had been abducted from her bedroom while sleeping and stabbed to death.

During recorded interviews, the boy made admissions that deeply disturbed detectives. He told police that he had intended to kill other children and described the murder as preparation for further killings. These statements became central to the prosecution case and later court proceedings.

Because the offender was a minor, police and courts were legally required to suppress his identity. He was referred to in legal documents by initials only, later becoming publicly known as SLD.

The investigation concluded with the boy being charged with murder. Given his age, the case proceeded under strict legal safeguards, but the seriousness of the offence led to a conviction and a lengthy custodial sentence, marking one of the most significant juvenile homicide cases ever prosecuted in Australia.

Psychological evidence and behavioural patterns

Psychiatric reports tendered to the courts described SLD as displaying severe personality disorder traits, self-centred behaviour and a limited capacity for empathy.

The court heard evidence that, following his release, SLD had approached nearly 200 women over a period of approximately 95 days. Some of these interactions involved women who were accompanied by young children. Experts described this pattern as reflective of delayed social development and poor judgment rather than typical adult behaviour.

Evidence was also presented referencing past violent conduct while in custody, including attacks on prison staff. These matters later formed part of the state’s argument that SLD posed an ongoing risk to the community.

Sentencing for the supervision breach

In December 2024, SLD was sentenced for breaching his supervision order at a hearing held in Sydney.

The District Court imposed a custodial sentence for the breach. However, because SLD had already spent a significant period in custody, he was granted immediate parole.

Despite this, he did not immediately return to the community due to further legal proceedings initiated by the NSW Government.

The NSW Government’s failed detention bid

In March 2025, the NSW Government applied to the Supreme Court under the Crimes (High Risk Offenders) Act, seeking to keep SLD in custody.

The state argued that SLD posed an unacceptable risk and sought an interim detention order. The Supreme Court rejected the application, ruling that the government had failed to prove to a high degree of probability that the statutory threshold required for continued detention had been met. The court also ordered the state to pay SLD’s legal costs.

Anonymity and the public debate

SLD’s identity remains suppressed because he committed the original offence as a minor. His anonymity has continued to generate public debate, particularly following his release and subsequent breaches.

Courts and legal experts have emphasised that anonymity is a legal safeguard rather than a reward, and that decisions about supervision and detention must be grounded in evidence and statute rather than public outrage.

Conclusion

The Bulli Beach breach case illustrates the lasting legal consequences of a crime committed in childhood and the difficulty of managing risk decades later.

The District Court’s ruling turned on careful legal interpretation rather than emotion or history alone. It confirmed that even brief public interactions can breach supervision orders when they involve prohibited associations.

More than 20 years after the murder of Courtney Morley-Clarke, the case of SLD continues to test Australia’s justice system, highlighting the fragile balance between rehabilitation, supervision and the protection of the community.

FAQs

Who is SLD in Australian court reporting?

SLD is a court-ordered pseudonym used to identify a man convicted of murder as a minor. His real identity remains suppressed because the offence was committed when he was 13 years old.

Why is SLD known as Australia’s youngest convicted Sld killer?

SLD was 13 years and 10 months old when he was convicted of murdering three-year-old Courtney Morley-Clarke in 2001, making him the youngest person ever convicted of murder in Australia.

What happened to Courtney Morley-Clarke in 2001?

Courtney Morley-Clarke was abducted from her family home on the NSW Central Coast and murdered. Police later established she was taken from her bedroom while sleeping and killed by her teenage neighbour.

How long did SLD spend in prison?

SLD served 22 years in custody, spending his teenage years in juvenile detention before transitioning into the adult prison system. He was released in April 2023 after completing his sentence.

What is an Extended Supervision Order?

An Extended Supervision Order is a legal measure under NSW law that allows high-risk offenders to live in the community under strict conditions designed to protect public safety after their sentence ends.

Why did SLD return to court over the Bulli Beach incident?

SLD returned to court after being accused of breaching his supervision order by approaching a woman and her child at Bulli Beach in October 2023. The case focused on whether his actions amounted to prohibited association.

What did the District Court decide in October 2024?

The NSW District Court found that one breach of the supervision order was proven beyond reasonable doubt. Two other alleged breaches were not established to the required legal standard.

Why did the Supreme Court reject the NSW Government’s detention bid?

The Supreme Court ruled that the NSW Government failed to prove, to a high degree of probability, that SLD met the legal threshold required for continued detention under the Crimes (High Risk Offenders) Act.